1.1 Top Troubles

Yet there are also serious challenges and concerns arising when one deals with today’s youth. For all who seek to help youth toward maturity – whether parents and relatives, pastors and youth workers, teachers, counsellors, social workers and health workers, or neighbours – there seems to be no end to the number of obstacles along the path. Suppose that one was asked by a local newspaper to attempt a list of the top troubles currently among youth. Here is a suggested list (in no particular order), using South Africa as an example (where I live and work; yet many items on this list are universal youth issues) (Codrington, 1999a; CASE, 2000; Gillis, 1994:96-169; Schwartz & Codrington, 1999:120-133; O’Donovan, 2000:205-216; van Greunen, 1994): fear, anxiety and stress, especially over: AIDS; death of parents; crime; failure in studies; relationships (friendships and dating) unstable or broken homes (65% have already experienced a divorce; only 23.5% state that they “definitely” spend regular meaningful time with their parents), depression, suicide, addictions – smoking, alcohol, and drugs, peer pressure, sexual immorality and HIV/AIDS (by far the number one youth killer, with estimates from 30% of young people to as high as 75% infected in some areas), crime, pressures especially in African communities: poverty (57.2% of black community); poor education; pressure regarding traditional practices (e.g., initiation rites and circumcision).

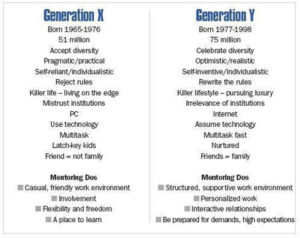

these goblins that seem to attack and devour our precious youth. In South Africa, among Christian sources alone there is a massive arsenal of detailed research and statistics on major youth issues, seeking to understand, evaluate, and offer workable solutions (Codrington, 1999a; Price, 1998). One can now consult in-depth profiles of “Generation X” (“Busters,” born between 1970-90) and “Generation Y” (“Millenials,” born between 1990-2005) for exploring any aspect of South African youth culture. Church growth analysts, demographic experts, and youth researchers are all being enlisted to give youth workers and parents the latest data on their teens. You can now receive up-to-date forecasts on every possible influence your teen will encounter in a typical day. As a result, many youth pastors/clergy are eagerly restructuring their entire ministries in both style and content to attract the postmodern young person (Zoba, 1997:18-28; Schwartz & Codrington, 1999:120-133; Codrington, 1999c).

these goblins that seem to attack and devour our precious youth. In South Africa, among Christian sources alone there is a massive arsenal of detailed research and statistics on major youth issues, seeking to understand, evaluate, and offer workable solutions (Codrington, 1999a; Price, 1998). One can now consult in-depth profiles of “Generation X” (“Busters,” born between 1970-90) and “Generation Y” (“Millenials,” born between 1990-2005) for exploring any aspect of South African youth culture. Church growth analysts, demographic experts, and youth researchers are all being enlisted to give youth workers and parents the latest data on their teens. You can now receive up-to-date forecasts on every possible influence your teen will encounter in a typical day. As a result, many youth pastors/clergy are eagerly restructuring their entire ministries in both style and content to attract the postmodern young person (Zoba, 1997:18-28; Schwartz & Codrington, 1999:120-133; Codrington, 1999c).Another evidence is the number of experts now starting to question standard diagnoses, such as the long-standing belief that low self-esteem is the root of many youth problems (Hewitt, 1998; Baumeister, 1993; Vitz, 1994). Recent news articles have  carried such titles as, “Losing Faith in the Self-Esteem Movement,” and “Self-Esteem’s Dark Side Emerges” (Chavez, 1996; Colvin, 1999). These articles recount examples such as exams where students’ performance was inversely proportionate to their self-confidence (Colvin, 1999:3), and research showing that “high self-esteem is more often associated with violence than low self-esteem” (Chavez, 1996).

carried such titles as, “Losing Faith in the Self-Esteem Movement,” and “Self-Esteem’s Dark Side Emerges” (Chavez, 1996; Colvin, 1999). These articles recount examples such as exams where students’ performance was inversely proportionate to their self-confidence (Colvin, 1999:3), and research showing that “high self-esteem is more often associated with violence than low self-esteem” (Chavez, 1996).

Should we then be surprised that therapists and sociologists cannot agree on the remedy for youth problems when they’ve never first agreed on a diagnosis? Everyone knows that diagnosis determines remedy. After declaring that the patient has an ear infection, the doctor does not reach for the throat lozenges. If he did, that patient would take it as a prescription to find a better doctor fast! Who would keep going to a doctor who applied useless or superficial remedies based on a faulty diagnosis? The success of the treatment depends primarily upon his skill in interpreting the problem. Surely at some point an unhealed illness drives us to question the diagnosis!

Doubtless, today’s analysts have insured that we have a detailed grasp of all the symptoms of each ‘disease’ found among our troubled youth. Now more than ever we stand staring with sadness at the infected, pitiful fruits dangling from the tree. Yet we still await evidence of true healing. We wait to see solid, lasting changes in the fruit our youth are bearing in their lives. One searches hard for a movement of youth who are not merely learning how to stay out of trouble by coping with their circumstances but who are being equipped with true wisdom for how to live all of life. One longs for more youth, as well as parents and counsellors, who are learning to recognise the root motives behind behaviour – the ‘whys’ behind what we do (Tripp, 1997:89-91). Until this is grasped, we fear that few youth will be well armed for the future waves of temptations to be faced throughout life (Tripp, 1997:127-166, 191-209; Hine, 1999:296-304).

– Tim Cantrell, President and Professor of Systematic Theology, Shepherds’ Seminary

– Tim Cantrell, President and Professor of Systematic Theology, Shepherds’ Seminary